Lessons from Use of Drones in the Ukraine War

Note: This post is an expansion of the original Opinion Blog published in DefenceConnect. All information in this story comes from the various open intelligence reports, as Ukrainian military and civilian population make extensive footage with their smartphones and publishing online. This makes it the first war of its kind, fought online as much as in the field.

Russian forces have used “greyzone warfare” (cyber, unmarked troops, Wagner Group etc) both in Eastern Ukraine and around the globe extensively for a number of years now. Using drones is an extension of this strategy.

US DoD classifies drones in 5 categories:

* Approximate translation from lbs

The focus in Ukraine has been substantially on smaller drones, classes 1-3, with US Congress pausing the sale of four MQ-1C Gray Eagle (class 4) drones that can be armed with Hellfire missiles, amid concerns of those expensive assets being shot down by the Russian forces and technology falling into Russian hands, as well as extended training time needed for the Ukrainian operators to fly those drones.

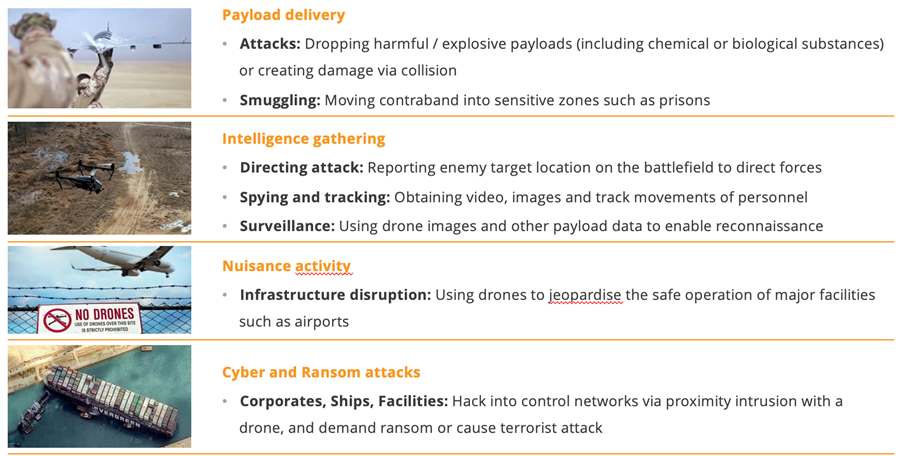

Smaller drones can be used in 4 ways in warfare: precise payload delivery (such as dropping explosives or kamikaze attacks), surveillance (scouting out enemy positions to send a mortar or otherwise coordinate an attack), nuisance / loitering and cyber/hacking (using proximity to enemy networks to hack in via a drone, and degrade/infiltrate the networks)

Figure: nefarious use of drones

Smaller drones came to symbolise asymmetric warfare, with a $3,000 drone able to drop a charge into a $5 million tank, destroying the tank and its occupants, without drone pilot being in line of fire.

Russians use the following small/tactical drones:

Orlan-10 (Special Technological Center, St. Petersburg) – most well-known drone, with reportedly over 2,000 units made

Eleron-3SV (Enics, Kazan),

Granat and the Takhion (Izhmash Unmanned Systems, Izhevsk),

Korsar (United Instrument Manufacturing Corporation, Moscow),

Zala-421 (Zala Aero Group, Izhevsk), and

Irkut-10 (Irkut company, Moscow).

Ukrainians also use drones, on the larger end, most famously the Turkish-supplied TB2 Bayraktar, following their success in Armenia against the Russian-supplied ground defence Pantsir systems and tanks (with Azerbaijan deploying the TB2s), as well as in Middle East. Immediately prior to the war, Ukrainians were in the process to set up a local manufacturing line for TB2s near Kyiv. However some of the used drones are designed and already being made locally in Ukraine too, such as:

UKRINMASH range of drones,

Ukranian loitering Munition ST-35 drones, and

KB Robotics Loitering Munition drones.

Loitering munition drones are a fascinating class of drones on their own, essentially a low cost flying smart munitions, popularised by AeroVironment’s Switchblade, launched from a tube in the field.

US Government has recently approved supply of AeroVironment Switchblade drones to Ukraine, for use in a range of scenarios including attacking tanks.

Image: summary graph of selected drones used by Ukrainian and Russian Forces

Why have Ukrainians be able to use drones so successfully?

Open-source intelligence shows numerous reports of Ukrainian drones dropping charges on Russian armoured vehicles and scouting enemy positions.

As BRIG Ian Langford pointed in the recent speech, the Russian side has expected a short war, won through a single domain, as opposed to combined-arms. This has allowed drones to do a lot more damage than they would otherwise could. Importantly, while the war showed drones (large and small) are an integral part of warfare going forward, they alone do not create a win – combined-arms, with a coordination between infantry, artillery, heavy armour, along air, sea, space and cyber domains.

And what about counterdrone/C-UAS?

There appears to be a divide between the full scale Electronic Warfare (EW) capability that Russians have, such as their on-vehicle system (which would be too much for drone jamming, too expensive to have lots of those units and they are vulnerable targets).

And on the other hand, the handheld and portable units, which appear from public reports almost “home-made”.

Such basic jammers are likely to lack safety protocols for the operator (Russians are not well known to consider safety features for their soldiers – consider them not investing in the internal lining between the tank shell magazine and the crew, which reportedly caused a lot of the publicised tank explosions where the tower flies off some distance from the body, when a shell explodes inside the tank and creates a chain reaction with the rest of the magazine). Back in the Cold War, there is a famous story of Americans and USSR having same class of a nuclear submarine, except the USSR boat was able to move faster… because the lead safety wall between the crew compartment and the nuclear engine was removed from the design, to help the speed. While western counterdrone devices go through full internationally accredited safety protocols (similar to what cellphone manufacturers do), Russian jammers are less likely to have the shielding and other design features for operator health. There is also a question of basic effectiveness – while jammers are originally an old technology (since WWII), there is a lot of IP in waveform/antenna design, jamming signal effectiveness, effective dissipation of heat and so on.

How effective are western counterdrone systems against Russian drones? A lot of Orlan-10 components appears to be Chinese, European or US made. Hence the established C-UAS systems would likely be highly effective, both in detection and defeat. With the Russian military-industrial base likely to be plagued by years of corruption and mismanagement, use of non-Russian componentry is not surprising. Similar to their tank production lines reportedly halted due to lack of componentry.

What are Australian takeaways from this?

Lesson 1: Drones and C-UAS are an integral part of combined-arms going forward

The use of drones (and C-UAS) in warfare is here to stay – Ukraine/Russian war will be in military textbooks around the world for next 20 years as a case study. With all the tragedy, devastation, death and loss, it is also a testbed for technologies in a military setting (first meaningful scale war for a long time).

Counter-UAS systems will become a critical component for heavy armour, such as tanks and howitzers, and will form a part of the soldier portable kits (along with small tactical drones themselves).

What is clear, is that both drone and counterdrone systems are making a meaningful difference in this war, and wars to come.

Lesson 2: The technology should be grown locally in Australia, as much as possible

Australia is currently the 12th largest defence spender globally by dollar amount (remarkable for a nation of 25 million), however most of the nations in the first 11 spots have extensive defence industries of their own – we are second largest importer of military kit in the world, after Saudi. And even Saudis are substantially aiming to do best they can in becoming more self-sufficient in defence, including their 2030 Plan.

We must become more self-reliant, on complex and expensive technologies, to sustainably continue being part of this select group. Much like Saudis being clear that their oil blessing will not last forever and they must build own capability, Australia cannot assume that digging iron ore and coal from the ground and swapping some of the proceeds for foreign-procured defence systems, is a long-term sustainable solution. In the event of armed conflict, our allies, as close as they are, will put themselves ahead of us, and we are a long way away, if supply lines get cut).

Thus we want to focus on being amongst best in the world in a limited number of key areas – as being average across everything is simply not possible with our population size. The good news is, our C-UAS capabilities (and, in a number of niches, drone capabilities) are already some of best in the world, and should be further grown through a wider adoption across Defence and Government key prospective targets for drone attacks and reconnaissance, such as bases, airfields, embassies, critical infrastructure and armoured assets such as tanks, personnel carriers, howitzers, vessels, and helicopters.

The levers have been substantially discussed already: Gate Zero contracts direct to the industry (this is a single best lever Defence has, to foster local industry), technology transfers where needed, encouraging STEM and complex engineering problem solving. We have become a nation of “above the line” defence businesses – writing reports for the Government, rather than building products. We need to emulate the US ecosystem and its successes, with the likes of DARPA, Program Offices (eg PEO Soldier etc), more formal and informal trials such as what the US DoD runs at the Yuma Proving Grounds (YPG), organisations such the US Air Force AFWERX and the like. Our Defence and Science Technology Group (DSTG) is a great institution, but we need more, much more, if we are to step into that elite group of top 10-15 defence nations, that our defence spending already places us around of.

We are witnessing a remarkable tectonic plate shift of Australia’s defence policy – lets make the most of it for our skills and self-sufficiency.